Strategies for Discussion

While reading is the focus of my class, discussion is another huge entity. My goal is for students to not only engage with a text, but also to be able to engage with each other to discuss the text and the ideas, issues, or questions that arise from the text. I provide my students with opportunities to discuss at various levels throughout each unit, all building up to the end-of-unit Socratic Seminar: mini-discussions, gallery walks, and snowball fights. To track and assess their participation during the discussions, I utilize Equity Maps, an application that provides statistics on each student’s level of engagement. Discussion is not only a vital part of my curriculum, but it is an extremely important skill that students need to learn in order to be successful outside of the classroom – for this reason, I utilize a variety of strategies to provide ample opportunities to practice and perfect this skill.

mini-discussions

Student-led mini-discussions were designed to provide students with more “at bats” at discussion prior to a Socratic Seminar. These discussions are similar to Socratic Seminars in that they are completely student-led, with no teacher facilitation or prompting, and I track their progress using Equity Maps (see below). However, these discussions are not as long as a Socratic Seminar, lasting only four minutes, and students do not move into an inner or outer circle. Additionally, students prepare for their mini-discussions the day of the discussion, having only five minutes to draft a claim and find supporting evidence. This discussion strategy provides students with multiple ways to engage in discussion, while also supporting and expanding students’ communication through speaking, listening, reading, and writing.

To the left are student work samples at varying levels:

Pages 1-2 — This lower student was unable to move past the answer stage, identifying no evidence. On the reflection, this student identified a difficulty in finding evidence, which showed their understanding of the problem and presented a goal for the next discussion.

Pages 3-4 — This mid student was able to identify relevant evidence but did not provide any commentary or explanation for the evidence. During discussion, this student did not speak, as noted in the reflection. This student sample shows the gap in finding evidence and crafting an explanation.

Pages 5-6 — This high student found strong evidence and crafted an explanation to support the initial claim. Higher students generally have more reflective answers at the end of the discussion, this student stating: “I struggle to word my claim to relate it to other’s claim/opinion/debate.

While the first page of the mini discussion shows me the gaps in understanding, particularly in the strength of finding evidence or crafting an explanation, the reflection page allows students to tell me exactly where they are struggling.

socratic seminar

To the right is a student work sample of a Socratic Seminar packet. Students receive this packet the day before our Socratic Seminar so they can complete their preparation work, which includes answering questions and finding evidence to support their claims (see pages 2-3). Students complete their preparation work on page 4, where they actually pre-plan their talking points and craft more specific explanations based on what they would like to say during the Socratic Seminar.

The next few pages simply include reminders about how we speak to each other during a Socratic Seminar. These rules and expectations would have been taught in 6th grade at my school and would be familiar to most of the students.

During a Socratic Seminar, students are split into two groups: an inner circle and an outer circle. Students in the inner circle have 10 minutes to discuss without teacher facilitation or prompting; it is completely student-led. During the discussion, observe and track students’ progress with Equity Maps (see below). Students on the outer circle are taking notes based on the discussion – both what is being said and how well the students are doing, as illustrated on pages 7-8. After the discussion, students in the inner circle reflect on how they felt they did (see page 9). Inner and outer circle students then switch, and the process is repeated.

At the very end of class, after both groups have had an opportunity to discuss, all students participate in a final reflection, where they have the opportunity to re-answer the essential questions based on what they learned from their peers, as well as to reflect on their own performance.

equity maps

Equity Maps, an iPad application that, according to its website, “provide[s] faster and more effective feedback for your students” and “effortlessly trace[s] and assess[es] your students’ interaction, performance, and involvement” during discussions. I use this application during mini discussions and Socratic Seminars to track and grade students’ participation, as well as to provide students with their own statistics so they can reflect and set goals for the next discussion.

This tool shows my commitment to exploring how the use of new and emerging technologies can support and promote student learning, while also providing me a convenient way to continuously monitor student learning progress and engage students in assessing their progress.

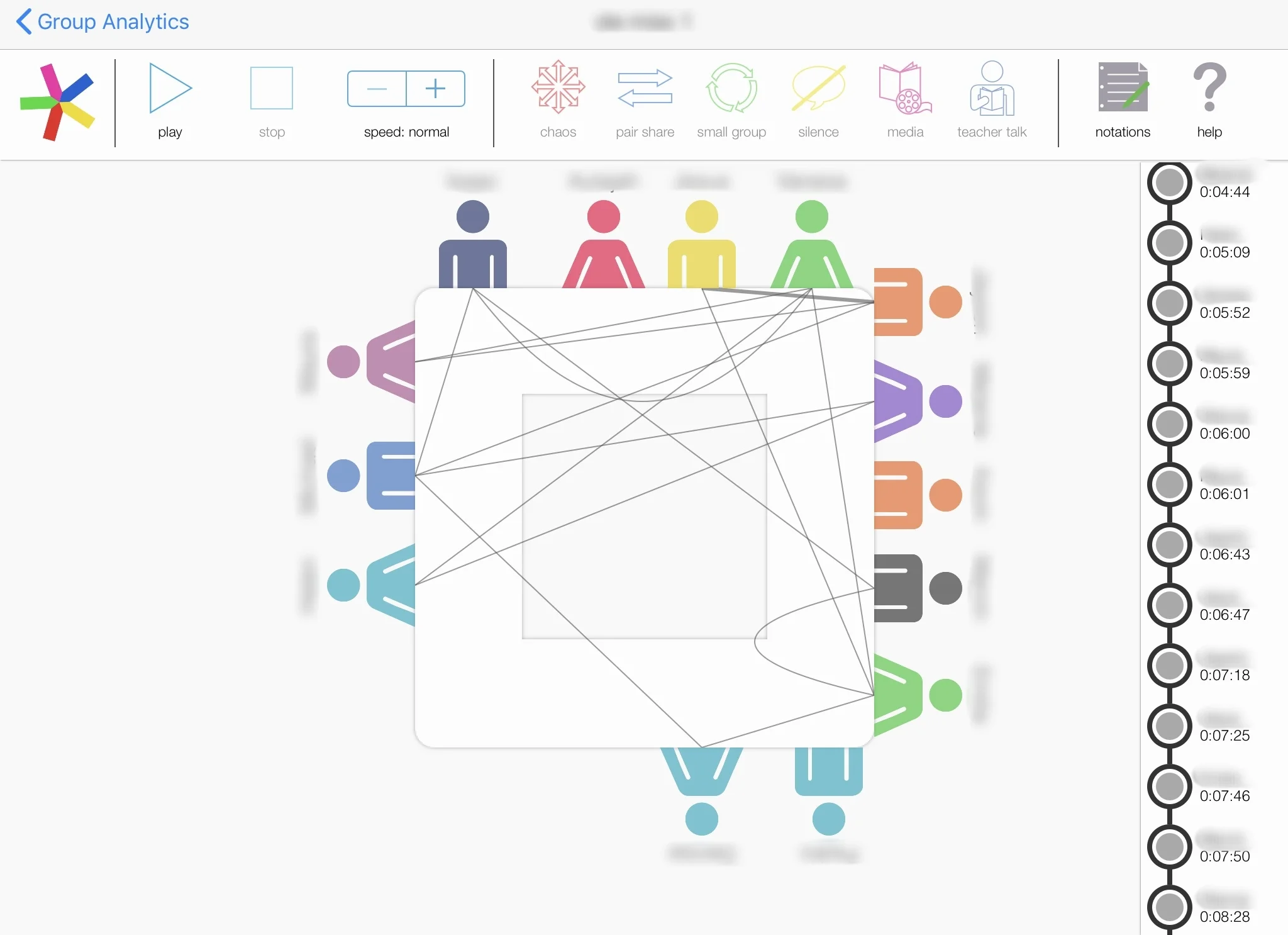

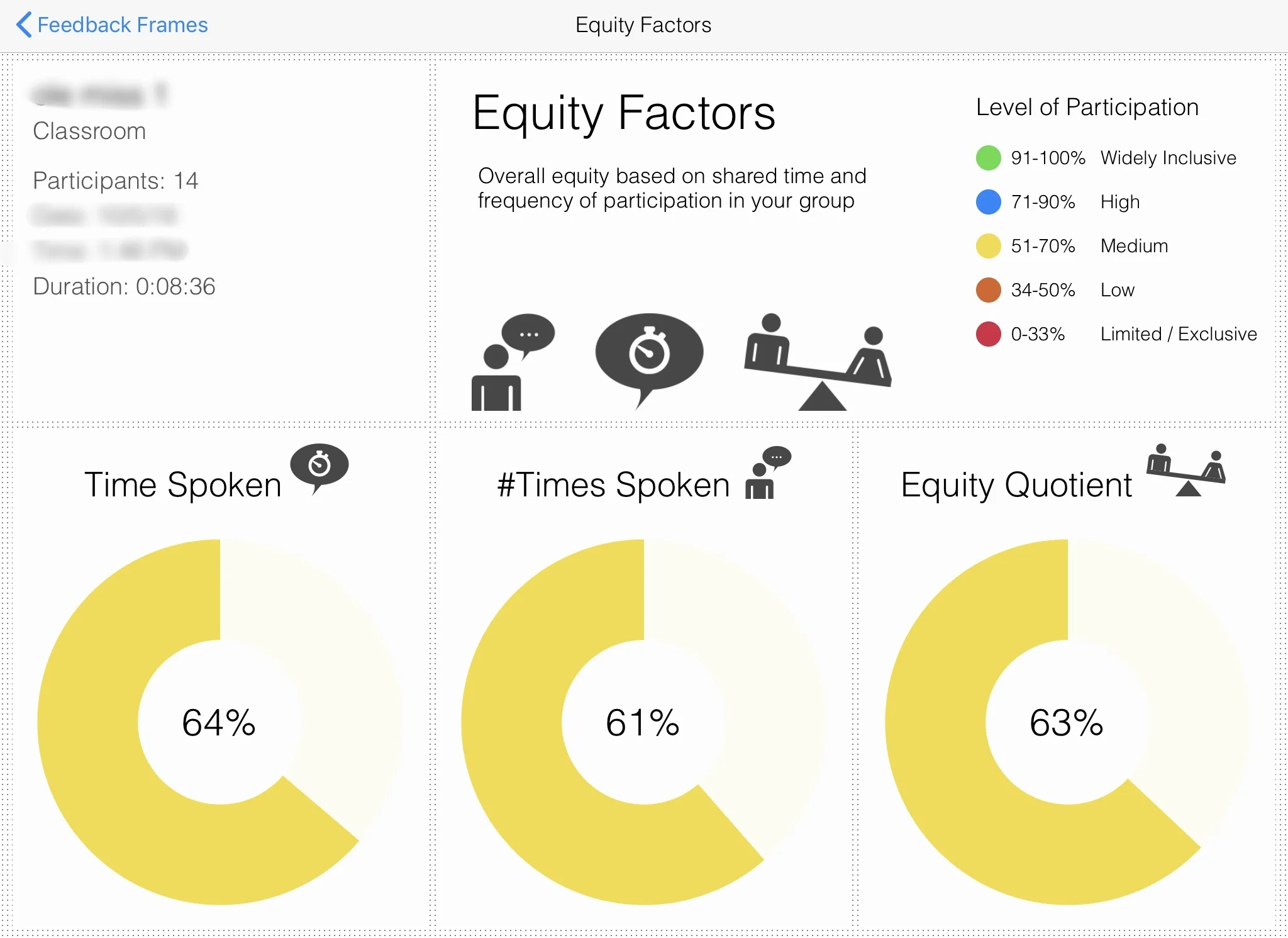

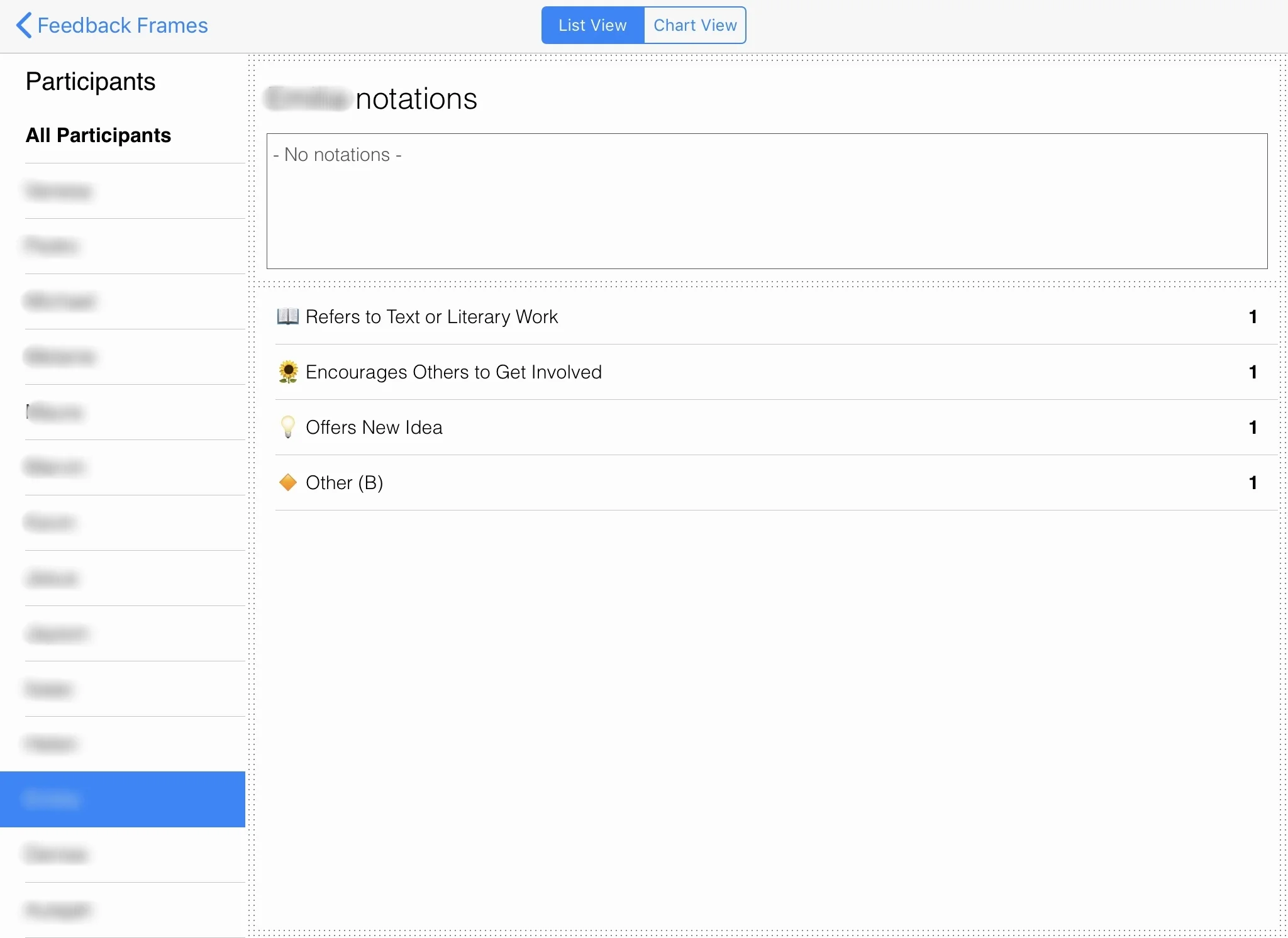

Above are several screenshots from a Socratic Seminar that was tracked using Equity Maps.

The Feedback Homepage (image 1) serves as the discussion stats homepage. Each section on this page takes you to a close-up analysis of a different aspect of the discussion.

The Discussion Map (image 2) is the literal map of the students’ discussion. It shows who spoke first, second, last, and so on, as well as the time each student spoke.

The Group Analytics page (image 3) shows the number of times each student spoke and what percentage of the discussion that student is responsible for. This page allows you to click through each student to get personalized statistics.

The Equity Factors page (image 4) analyzes the overall level of participation for the discussion as a whole. This is a great page to show students who can set a collective, class goal to improve their “rating” in the next discussion.

The Student Notations section (image 5) is provided to students, as it shows more about the quality of their comments during the discussion. Students can see if they used evidence, if they asked strong questions, or if they brought their peers into the discussion. This section is created by me during the discussion.

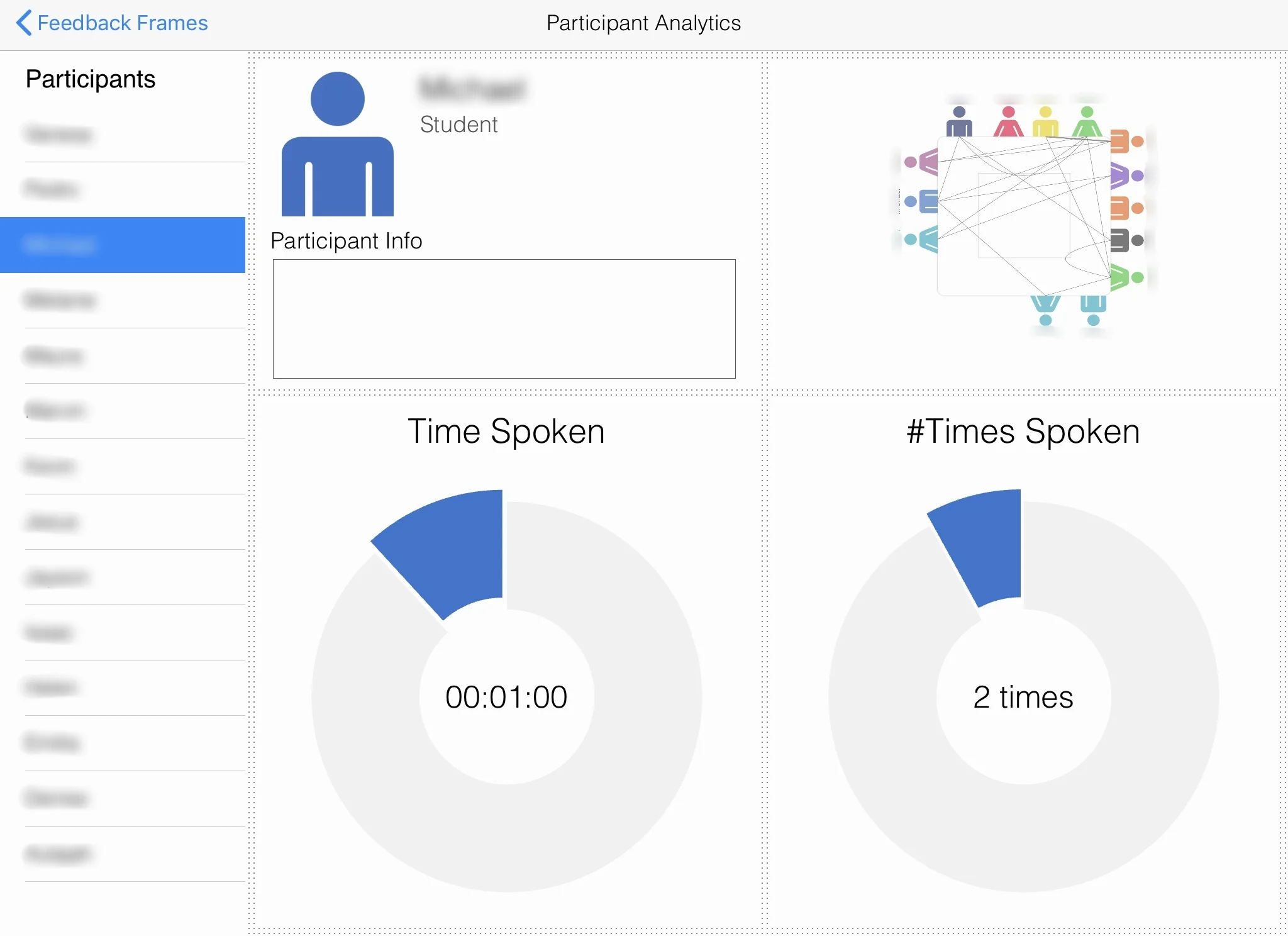

The Participant Analytics (image 6) is another version of the “Group Analytics” page, just at a micro-level. Each student has a page that shows the number of times they spoke and the duration of their total talk-time. This is great page to print out and distribute to students.

Gallery Walk

Gallery walks provide an opportunity for students to engage in a silent discussion, see pages 1-2 to the right. Students will walk around a room and read the questions written on different chart papers. They will then contribute to the discussion on that page, either by adding their own ideas, building on the ideas of another student, or even agreeing and disagreeing with what their peers have written. The expectations for gallery walk discussions are the same as verbal discussions and generally produce reflective and respectful work.

Pages 3-6 in the document to the right show the final chart papers for a gallery walk discussion based on the theme of the immigrant experience in My Antonia. Students were asked to evaluate how specific characters helped to develop the theme, and then used what they learned from their peers during the gallery walk to answer the essential question: “How does the author use the characters to develop her commentary on the immigrant experience?”

I have found that students’ answers greatly improve after seeing what their peers have to say about a topic, and students value learning from each other and gaining perspectives from their peers. This is another strategy in which I, as the teacher, vary my instructional role and stimulate a discussion by asking specific, targeted questions.

Snowball fights

Snowball fights, while one of the more unconventional types of discussions we have in reading class, provides students a fun, alternative way to have a silent discussion. Snowball fights are similar to a gallery walk, in that students are answering a question on paper and then building on the ideas of their peers.

In the example to the left, students first watched a TEDTalk by a young girl who discussed her experience as an immigrant in America. This video directly aligns with one of the themes in our text, My Antonia. Students then wrote their response to this video on a blank sheet of white paper. For this particular discussion, the question was fairly open-ended because I knew that many of my students were themselves immigrants or had parents who were immigrants, and I was curious to see how they would respond to the topic.

Once students have crafted their response, they crumple their paper into a “snowball” and have 10 seconds to throw their snowball across the room, see page 1 to the left. I then begin to count down from 10 and by the time I get to 1, students must have a new snowball in their hands, as shown on page 2. Students carefully open their snowballs, read what their peers wrote, and respond.

Pages 3-6 are examples of the responses students made to the TEDTalk, as well as to each other. I was particularly moved by several of the students and applauded their vulnerability with each other — especially those who shared their personal experiences.

One student, who is an immigrant and ESL student and generally struggles to participate, wrote:

“This make me feel so sad, and I think that because my dad did everything for me to make me happy and do everything to get me this far in life and I thank my dad for help me learn and I love him" (see this student’s answer and his peers’ responses on p. 3 to the left).

Responses like this solidify in me the importance of using a range of strategies so that all students — not just those who are outspoken or academically high — feel they are in a space they can learn, grow, and engage. This type of discussion allowed students to access the content by using their family and community experiences, which developed their interest and investment in the novel. These types of unconventional discussions, including Gallery Walks, deepen learner understanding and stimulate their curiosity — they provides students discussion outlets that are less intimidating than speaking in front of a room of 30 people and teach students that their are multiple ways they can communicate their thoughts and ideas.